2200 words, 11 minutes.

Engineering, Vol. 62, December 18 1896.

“In 1882 I was in Vienna, where I met an American whom I had known in the States. He said: ‘Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility.’” - Hiram Maxim.

Selling arms during an arms race is such an interesting topic it warrants its own post. There are market dynamics and game theory to be explored if you’re the one with the arms, have no competition, and a market of large and small regional “powers” vying for supremacy. It may pay you to give away your product for free at first. To small, weak, participants who wouldn’t have been able to afford it anyway, simply so that they may demonstrate the product’s effectiveness. Larger buyers with deeper pockets and more to lose can always be approached later.

BackChannel was a company I founded with former colleagues from CheckPoint and UUNET. We captured “exhaust gasses” from the Internet and turned them into valuable, actionable, signals intelligence for network operators. We did this in order to help those operators adopt Yield Management as a strategy for increasing their profitability. We used automated penetration testing techniques, big-data, and machine learning, at Internet-scale. We worked to build a strategic software platform.

Then we tried to start an arms race with it.

This is the story of that company, our product, and what I learned about human nature while selling it.

The Gathering Storm

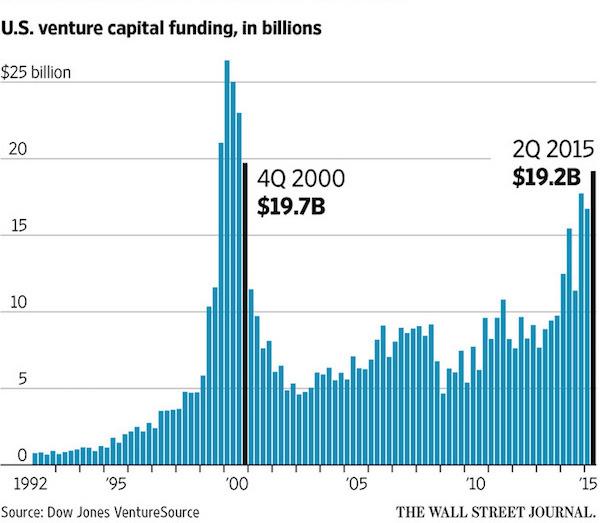

In the early 2000s the Dotcom crash was about to strike. The telecommunications sector was experiencing a glut of supply and the phones had stopped ringing on the sales floor. It wasn’t immediately clear to me, but this was the end of an exhausting and exhilarating 5 years of hyper-growth building the world’s largest Internet Service Provider. I’d recently switched from being a quarterly driven Security Product Manager, to working with the Chief Scientist on the product pipeline 2-5 years out. My last big launch was our Global Managed VPN service, it had taken almost 2 years from concept to reality. Looking 2-5 years in the future felt like a good place to search for the next big thing.1

The hush from sales told me that very soon nobody was going to be interested in “2-5 years out”. The event horizon was about to shrink dramatically.

I didn’t predict the crash. After all, money was still pouring in from investors, but it seemed like a good time to take my equity and leave. I went to work for one of the world’s most respected Venture Capital firms as an Associate, helping others build high-growth technology companies.

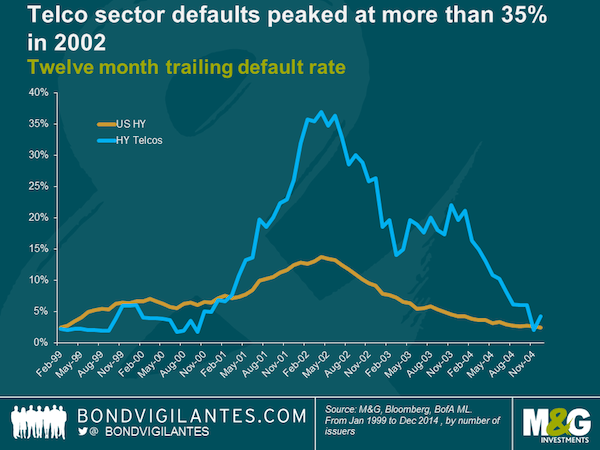

After a few years I returned briefly to telecommunications for some turnaround work. I found network operators attempting to do business in the same way post-crash as they had done pre-crash. On the outside the news was of bankruptcy, class actions, and more than a few criminal prosecutions. Inside, these companies still seemed oblivious to the fact the world had changed. The signal might have reached the brain, but it was taking a long time to get to the feet. Margins were reduced, competition fierce, fundraising difficult and expensive. The growth spurt gone. Focus shifted to profitability. A cold wind which had begun in the US now turned east, to Europe.

If you were running one of these network operators you had limited options. The debt was due. You were still managing the shift from legacy services to the new IP-centric world. Prices were falling as competitors attempted to continue growing their top-line with analyst expectations. VCs turned off the cash to startups buying bandwidth and hosting.

There were only 3 ways out.

- M&A.

- Refinance.

- Restructure.

If (1) then you are better off being the consolidator or acquirer, than being the acquired. Particularly if you are a member of the C-level team. (2) was simply not a realistic option for most carriers, unless they had a uniquely understanding investor. (3) was going to be a long and uncomfortable journey even for the best management team. Network operators are like oil tankers; they take a long time to turn around. Nobody is paying much for a tanker which costs more to run than it makes in oil deliveries.

The problems in the telecommunications industry at the time were not new. One could draw historical parallels with railways, airlines, postal services, even the theatre business.

- Large fixed asset, paid for with long-term debt, like an aircraft.

- Finite capacity. Only so many seats on the plane.

- Low marginal cost of onboarding a new client.

- High cost of periodic upgrades to capacity (a new aircraft or route).

- Oversupply, slowing demand.

- No graceful market mechanism for removing excess capacity.

It was 2005. Network Operators were strongly incentivised to become profitable. Cutting costs would be their first move, but they would struggle for an encore. Unlike aircraft or railways, fibre networks do not rust or rot. Not on the timescales we are talking about. It was an existential crisis.

Wunderwaffe As A Service

What if Network Operators had a way of determining who the most profitable prospects were long before customer acquisition? What if they could profile the customer-base of their competitors to see who those customers were and what they had bought? How would it change their profitability if they targeted the sales force on only the most profitable accounts and not the less profitable ones? What if they could specifically target customers whose geography precisely matched their network reach, or fit with their product portfolio?

Yield Management is a discipline used by airlines, rail operators, and others to maximise economic profit from an asset of fixed capacity. They do this by either offering differentiated services (business class versus economy) or by targeting a specific part of the market (frequent travellers versus infrequent, long-haul versus short-haul). While some telecommunications firms have a B2B/B2C split, none were doing anything significant in terms of yield management. The concept had been discussed in academia since at least 20012.

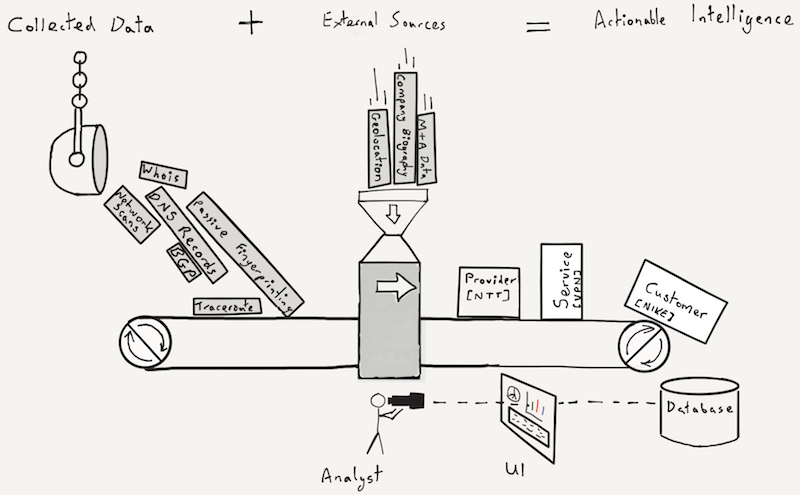

BackChannel was a Software As A Service platform I designed along with former UUNET and CheckPoint colleagues in 2005. It was built to give network operators Yield Management. It did this by gathering data about the Internet and augmenting that data with company biographical information.

- Backbones and tail circuits.

- Routes and peering points.

- Bandwidth, circuit utilisation, latency.

- Ownership, customer, operator.

- Services, service providers.

- Reliability and geolocation of the above.

BackChannel presented this information within a context of:

- Customers (usually corporations).

- Telecommunications services (connections, hosting, VPNs).

- Providers (usually network carriers or hosting companies).

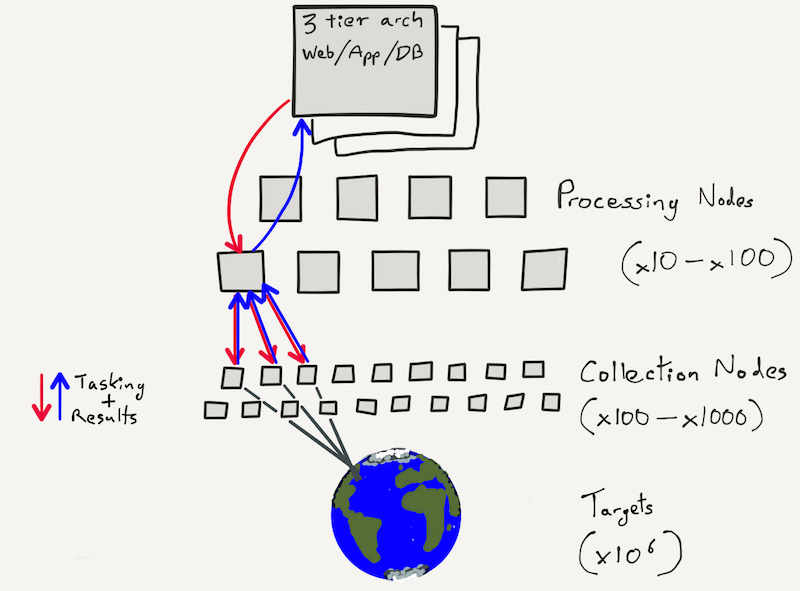

Sales and marketing executives used it to plan their activities within a market, geography, or individual account. Want to know who an organisation buys from and what they buy? BackChannel could tell you. It did this using a geographically distributed network of data collectors, an intermediate tier of processing nodes, and central machine learning and big-data analytics. The central system provided reports, dashboards, and query interfaces. We were tracking about 1.2 million organisations and hundreds of service providers worldwide.

BackChannel captured exhaust gasses from the world’s networks and turned them into actionable signals intelligence for telecommunications companies, so that they might survive in an environment where profitability was paramount.

That was the positive sell. Restructure sooner, refocus on profitability, review M&A opportunities as buyer or seller with unique insight into your fitness and the fitness of others.

Engineering The Arms Race

There was another side to BackChannel. A darker side. Yield Management has been a decisive weapon in every industry to which it has been applied. Those that mastered it survived and thrived. Those that didn’t, perished. This means any product capable of enabling Yield Management is an arms race product. If you get it early you can take out the competition with an attack they cannot easily counter. If you get it late then you regain balance and can hold your position. If you never get it, “for you Tommy the war is over”.

Every company wants one of two things. Either they want a competitive advantage, or if they can’t have that they want a level playing field. - Our 1st customer.

To paraphrase Hiram Maxim, pictured at the top of this post, we would be the ones to “enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility”. Not just the Europeans either. The Telecommunications bust was global and 10x larger than the dotcom crash. We would be an equal opportunity throat-cutter.

Enterprise sales cycles are slow. Selling to network operators even slower. BackChannel’s SaaS model helped, but our service touched sales, marketing, and finance, none of which strictly speaking have technology budgets. Nor were they used to adopting new products and services. We used the arms race metaphor as persuasion tactic. It went something like this:

- Your debt is due.

- No funding incoming from investors.

- Consolidation is the inevitable result.

- Better to be consolidator than consolidated.

- Better to demonstrate profitability to an acquirer at least.

You can stop selling me. I’ve bought it. Tell me how you are going to deliver it. - CMO, world’s 8th largest network operator.

Sitzkrieg!

Almost all significant network operators are public companies. Quarterly driven. Only those at the very top of the organisation think strategically. The arms race part of our pitch went down well with C-levels (once we’d reached them), but it cut little ice with those below. Nobody refuted it. The logic was simple. The telecoms crash was an observable phenomenon by then, but to push that part of our message upwards was to suggest the emperor (CEO) had no clothes. While we continued to steadily acquire customers with the positive part of our pitch, we did not trigger the surge in demand we hoped-for. Without an existential threat of an arms race, there was no stampede. We continued the slow, laborious job of approaching prospects and closing them. Without the relentless dynamic of the arms race on our side, it was hard.

Lions Led By Donkeys

Ultimately the network operators were not predatory enough. Even when presented with an opportunity to remove a competitor from the field, most preferred to sit it out. The management teams were streamliners, cost-cutters, rationalisers, and right-sizers. Sure enough they failed to find an encore and were eventually acquired by larger competitors, often at knock-down prices. The 8th largest in the business recognised this, and even acquired a smaller operator largely because they had a more dynamic, virile management team. While we could put a Maxim gun in their hand, they lacked the will to use it.

The prospect of selling arms during an arms race faded. BackChannel went on to play a role in 2 M&A deals (one network operator, one cloud service provider), and continued to supply customer data to a number of clients for several years. It was a slow-but-steady affair.

Between 1908 and 1913 military spending of European powers increased by 50%.

There was to be no such bonanza for BackChannel.

Refighting The Last War

Network Operator management teams were not incentivised to be acquisitive, to take advantage of weakness in others. For them it was too much career risk for too little personal reward. They adopted a “wait and see” approach to market consolidation. The M&A we predicted did happen, but it was a war of attrition, not a blitzkrieg. With hindsight of the personalities, corporate culture, and incentives, could we have changed things? What would we have done differently?

- Firstly I’d go directly to shareholders. For smaller network operators this includes Activist Investors and Vulture Funds. For PTTs it means the pension funds. Activist Investors were awake to the possibilities. We had already seen off one during my time in Venture Capital. Perhaps there was scope for partnership. BackChannel data supporting or enabling an activist agenda.

- Secondly I’d forgo traditional marketing to prospects, and begin a campaign of propaganda to exert maximum pressure on individual board members within network operators.

- Thirdly, I’d enlist the analyst community and journalists in the above endeavours, for the mutual benefit of both.

- Then and only then would I serendipitously approach network operator management with a way out. Possibly with a meeting brokered by an analyst. At that point they have little option but to pull the trigger.

Everyone wins.

- Shareholder makes bank.

- Customer improves profitability.

- Analyst gets kudos for calling it (and potential M&A advisor fee).

- Journalist writes the story where management is the hero.

- Customer can afford to spend more on advertising, conferences.

- Arms dealer disappears quietly with a cheque.

Would it have been enough? We’ll never know. It’s an approach Hiram Maxim and his legendary VP Sales Basil Zaharoff would have approved of. Zaharoff invented it. It was called Systeme Zaharoff and was used repeatedly to sell everything from submarines to aircraft. It was a winning system that made Zaharoff one of the richest men in the world.

There’s one thing of which I’m sure. I’m not done with arms races, or strategic software. Not while technology has the potential to change the course of history. Meanwhile if you need a global signals intelligence platform, you know where to find me.

-

I determined the next big thing to be Content Delivery Networks, along the lines of Akamai then or Cloudflare now. Not only would these enhance existing customers experience but would have allowed us to extend our brand values of quality and performance from our own backbone across the backbone of others. I’d hoped this would allow us one day to beat the competition through bundling and cross subsidy of both physical network and CDN. ↩︎

-

Yield management for telecommunication networks : defining a new landscape. Humair, Salal; Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Operations Research Center. ↩︎