1400 words, 5 minutes.

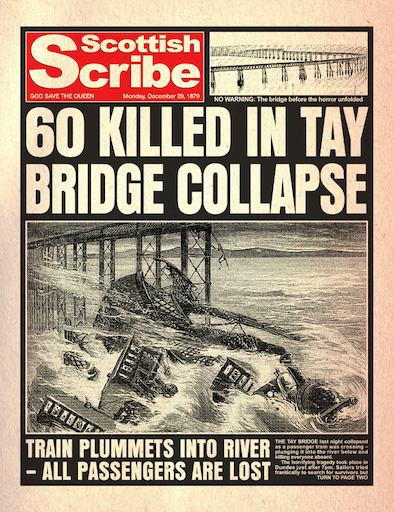

The Tay Bridge disaster occurred during a violent storm on 28th December 1879 when the first Tay Rail Bridge collapsed while a train was passing over it from Wormit to Dundee, killing all 70 people aboard.

The Tay Bridge disaster occurred during a violent storm on 28th December 1879 when the first Tay Rail Bridge collapsed while a train was passing over it from Wormit to Dundee, killing all 70 people aboard.

It is widely accepted by engineers that disasters teach us more than successes. Said another way, we don’t learn from the bridge that stays standing. After the Tay Bridge disaster there was an investigation. It covered everything from the design of the structure (flawed) though to the quality of components (variable). The type of iron used (inappropriate) and the maintenance regime of the operator (inadequate). Finally the commercial pressures under which the project was conducted (can you guess?) and the relationship between the various engineer’s egos and personalities involved (do I need to say?). If you can find the time take a look at the report, it will not disappoint. It was only 8 months from disaster to published conclusions. How does that compare to public enquiries today?

Although Tay was not the last bridge to fall, none of the those built in the UK after it, had such problems.

That’s how much of a watershed moment a disaster can be for engineers.

Much of what the software and technology industry does today is invisible. Sometimes (at least initially) even our failures go unseen. Sooner or later a significant number of people will be killed each year by software. I don’t mean by Hollywood-style hackers, terrorists, or sentient AI gone mad. I mean by simple, avoidable, routine failures of software engineering. Those of you who are not familiar with real-time or safety critical systems may be surprised to learn that many people have already been killed by software. Software professionals even have their own “Tay Bridge Disaster” which is taught in universities.

Software’s Tay Bridge

The Therac-25 X-ray machine killed several people around the world. All of them died a prolonged and horrible death by massive radiation overdose. The reason? A race condition. An unplanned-for coincidence, made deadly by the conscious design decision to remove an old-fashioned safety interlock. Flawed software, whose vendor had such faith in their product that they refused to believe there could be anything wrong with it even as the casualties mounted. Fortunately such medical devices are expensive, there are few of them made, and there are even fewer vendors making them. They have long development periods and are sold into a regulated industry with watchdogs, safety boards, and follow-up. Once the machine’s problems were understood, it wasn’t hard to track the units down and prohibit their use.

Therac-25 shouldn’t have happened. However the comprehensive investigation at the time and afterwards benefitted the whole industry.

The new exciting wave of medical devices are not £3m MRI scanners, or even £50k x-ray machines. They are desktop, desk-side, or handheld objects. They are manufactured more cheaply with a shorter service lifetime. They may not carry radioisotopes, but they do monitor and control doses of drugs, or provide data used to determine your treatment. I’ll bet every single one of them has more lines of code than the 1980s-era Therac-25. In the future even the stethoscope and thermometer will be smart, wireless, digital systems, tagging their readings with your patient ID. Let’s hope vendors have learned the lessons from Therac-25. Today it isn’t just careless programming and accidental race conditions we have to worry about. These new devices are connected, use open networking protocols, and their software may be assembled from different sources of differing quality. Security vulnerability should be a major concern for all such device manufacturers.

Your Daily Invisible Disaster

Not all IT disasters are so dramatic nor involve loss of human life. Not all of them are purely down to a misplaced line of code or unplanned-for input. Most of the large-scale failures in the industry are failures to deliver. Failures of projects. Outsourcing failures, upgrade failures, migration failures, ERP, CRM, SRM failures. The truth is that every single day a “Tay Bridge” falls down, a project is cancelled, a crisis meeting is convened, a deadline extended. Most don’t make the news, many aren’t even widely known within the companies involved. Cost overruns are hidden, projects are merged to disguise failure, changes in priority are blamed for lack of progress. You know it because you’ve seen it.

These “Tay Bridges” fall in silence and in darkness.

When dawn breaks there is no wreckage for the public to gawp at.

No board of enquiry is convened.

No institutional lessons are learned.

The cycle continues.

Nobody dies on a failing CRM project. At least not so far as I know. So why should you care? Everyone still gets paid.

You should care because within government, the only sector where failure gets any real coverage, I count £20b in failed IT projects over the last decade alone. Because within publicly quoted companies such failures are a bonfire of shareholder value. Because the ability to deliver technology projects will become the determining survival factor for many companies. Finally, you should care because if there is a skills shortage (or as I prefer to say, a talent shortage) and talent is tied-up with moribund IT projects, the lost opportunity cost to business is vast.

Do you know what the largest IT project failure was at your firm, sector, country?

Do you know what the second largest was?

Do you know why those projects failed?

Breaking The Cycle

While there have been attempts by very distinguished individuals to cast light on such failures, I don’t see much evidence for them being successful at improving outcomes. The failure rate for IT projects remains shockingly high. All the books, courses, and well-kept project logs haven’t made much difference. I conducted a quick and totally unscientific survey of why this is:

- Material not detailed enough.

- Not technical enough to apply to me.

- Too dry, too sterile to really engage with.

- Ignored all the human factors.

- Too focussed on problems rather than lessons.

So what works? What grabs attention? What carries over distance and persists? What might challenge individuals and organisations to change their behaviour? What doesn’t just hi-light failure but also teaches success? The answer has to be increased transparency and accountability. No individual wants to be associated with failure. No organisation wants to be associated with non-delivery or sharp practice. For projects that were ill-conceived from the start, transparency would impose a significant reputational cost to those involved.

What would such transparency and accountability look like? How would I characterise content capable of changing the outcome of such projects?

- Attention grabbing.

- Detailed, technical enough.

- Pulls no punches, undiluted, unadulterated, not-sterilised.

- Includes detail about names, personalities, temperament, politics.

- Contains analysis and solutions, not just problems.

This sounds a lot more like WikiLeaks and less like a traditional textbook. Something like a curated, annotated version of Phil Caplan’s infamous dotcom era website, rather than a module on a PRINCE2 course. WikiLeaks content is what travels and persists today, it’s a format more people read. Short, serialised, immediate, easy to digest, easy to share, regularly updated.

It could be a blog.

A blog taking anonymous submissions from you, on today’s collapsing bridge.

Names, companies, suppliers, vendors, integrators, managers.

I wonder where we could find such a blog?

Final Thoughts

I’m guessing you didn’t have time to read the Tay Bridge report. That’s OK. If you did you’d know that the designer and project manager, the man ultimately blamed for the disaster, was an interesting fellow. His self-professed forte was “light and cheap”. Victorian’s weren’t shy of using the word cheap when talking about engineering. One characteristic of all his projects was low CAPEX. This made his client very happy. The other characteristic was much higher OPEX needed to maintain them safely. His clients didn’t have Gartner to tell them about TCO. Mostly it didn’t matter. Mostly.

If you find yourself on a failing project, squandering tens of millions of pounds and hundreds of man-years of talent, pause for a moment. Think about the fact that almost 140 years ago, civil engineers stopped building bridges that fell down. They stopped building them because the failure of one bridge was laid bare so publicly.

For those of you catching a train soon, do have a safe journey.