4095 words, 16 minutes.

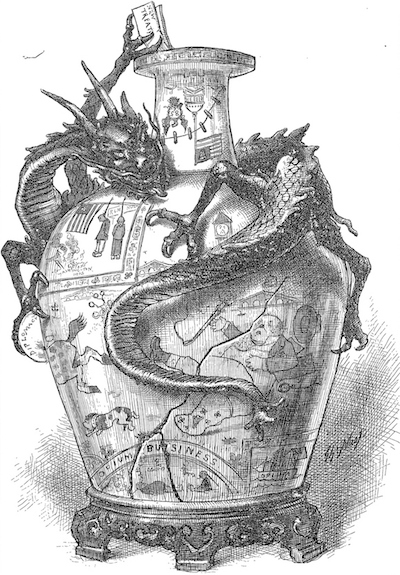

A Diplomatic (Chinese) Design Presented to the U.S. – 12th February 1881 by Thomas Nast, for Harper’s Weekly.

I rarely mention vendors here, so this post is an exception. It’s the second in my “Projectionist” series. The series is ultimately about power and the great forces and constraints shaping our world. I’m going to talk about 5G, Huawei, China and the consideration the UK and her allies are giving to the use of Huawei’s products in national mobile networks.

The 5G episode is just the latest in a long-running saga that goes back to the early 2000s when I first met Huawei’s agents. The company had an agency agreement with a businessman who was acting as their representative in Europe. They were selling clones of Cisco’s SME/CPE routers. Today China in general and Huawei in particular, is capable of much more than simply copying.

Disclaimer

- I’ve no part in the evaluation of 5G equipment.

- I’ve no colleagues in government working on the 5G matter.

- I don’t stand to benefit from any particular choice of 5G vendor.

So why should you care what I have to say?

- I’ve former colleagues working at Huawei, their competitors, and mobile network operators.

- Some of those people are involved in 5G.

- I spent my early career at the worlds largest Internet Service Provider.

- I sat on the Security Working Group of the GSMA and 3GPP/3GIP during 3G’s formative period.

- I’ve worked cases where a network operator’s core or edge equipment was compromised at the firmware level.

- At least one was almost certainly the work of a state-directed adversary.

- I keep an eye on the fortunes of the UK and her allies and consider myself a foreign policy realist.

This puts me around the midpoint between Huawei, the network operators, and the UK’s national interest. Not a bad place from which to make a post.

Why Huawei Matters

The world is upgrading its mobile networks to 5G. This is the 1st major upgrade since 3G. 4G was a step not a leap. 5G provides the benefit of increased speed, reduced latency, better reliability, and superior performance in crowded environments. It will better support the adoption of the Internet of Things. Some new features will have a direct impact on end-users, others will allow the network operators to run infrastructure more efficiently. 5G even holds the promise of improving your battery life.

5G needs somewhere between 5x and 20x the number of base stations when compared to 3G. This is due to physics and the reality of signal attenuation and the management of interference. An immense level of investment is required on the part of the mobile operators. Once their networks are built, those operators must extract maximum value from them to generate a return for shareholders. The stakes for these operators couldn’t be higher.

If 5G’s rollout is bungled in a country as a whole, either through delays, market failure, or some problem with implementation details, that country will suffer. That suffering will be felt in every smart city, hospital, and smart-home. It will in some small way impact every drone delivery, wearable device, and transport system. While it’s an exaggeration to say 5G is as important as electrification, one might compare it to the upgrade from “A” and “B” roads to Motorways in the UK.

Developing carrier-grade equipment for 5G is a huge commitment. It takes thousands of people working for years in software, hardware, with standards bodies, and in legal and regulatory. Scientists and engineers must deal with problems like signal strength mapping and RF testing environments. There’s the odd public health concern to be addressed too. Very few companies have pockets deep enough and shareholders patient enough to see through such a development. In contrast to present-day Silicon Valley, 5G network equipment vendors have lots of greybeards as-well-as the usual crop of young PhDs. You can’t MVP your way to an integrated 5G platform in a year.

There were never a huge number of suppliers in this market. The barriers to entry, economics, risk, and practicalities of implementation saw to that. Consolidation took care of Nortel, Motorola, Lucent, Alcatel, and Siemens. The UK’s only might-have-been, Marconi Communications, didn’t survive the last big UK equipment bonanza. BT chose Huawei for the fixed-line 21CN contract. Marconi was initially Huawei’s joint venture partner in that deal and the favourite to win. In the end, Marconi won nothing and perished. Huawei went their own way with a separate bid which somehow came in at exactly the right price.

Because of these challenges, there are only a handful of serious 5G network equipment vendors. Huawei, Ericsson and Nokia are each expected to take about 25% of the world market. The remaining 25% will be divided up between Samsung, Cisco, and a few smaller participants. This is a predictable effect of market forces, technical challenges, and capitalism. It’s why Huawei matters.

Recent Developments

Attributed to Otto Von Bismarck, 1933. Probably apocryphal.

Watching the UK/Huawei review process hasn’t been reassuring. I’ve kept a thread:

I always found UK Gov's enthusiastic embrace of Huawei quite mind boggling. https://t.co/OVDj1TUjcY

— Nick Hutton (@nickdothutton) December 27, 2018

- A course was charted then reversed, only to be reversed again.

- Positive progress was signalled, then negative, then positive.

- Various individuals stepped out of government into Huawei.

- Leaks, briefing, counter-briefing, rumour.

- The Defence Secretary was fired.

This can only mean one thing. Politicians, trade envoys, the security services, and vested interests are all pulling on the ship’s wheel. I suspect they lack even an agreed framework for getting to a decision. Perhaps unsurprisingly no decision has yet been forthcoming.

- More delays were announced in Parliament on the 22nd of July.1

- The Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC) published an annual report.2

- UK Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) made a statement 19th July.3

- UK network operators have already started buying 5G Huawei equipment.

Each of the above can be summarised:

- Politicians have stalled for more time.

- Huawei’s software quality, security, development process, and ability to improve these things is poor.

- Delaying the 5G decision is damaging the UK’s international relationships.

- Network Operators can’t and won’t wait any longer.

HCSEC Report

The report is clearly worded and anyone working in the field of Cyber Security will find it an easy read. The first few pages are sufficient. It’s plain to see that both the products and the processes used in their creation are poor from a security standpoint. Read the report or this article. I’ll single out just one quote.

"…it is not possible to be confident that the source code examined by HCSEC is precisely that used to build the binaries running in the UK networks." - HCSEC Annual Report, March 2019.

HCSEC has been working for 8 years and can’t even be sure the source code they are shown is the same as that used to make the product in question.

ISC Letter

The ISC letter has several problems. If this is really how the ISC thinks then it may benefit from an assessment of its own.

Vendor Diversity Fallacy

The letter is at pains to push the benefits of vendor diversity, both within a telecommunications network and the market in general. Superficially this makes sense.

But.

Vendor diversity is not a strength if one vendor significantly underperforms the rest, and if you have the option of identifying and excluding the underperforming vendor. I’m not talking about a malicious vendor, simply one whose security is poor. One could even argue that the inclusion of the underperformer is a signal to the rest of the market that they needn’t worry about security and can drop their own standards. We know from both the HCSEC report and independent analysis that Huawei is closer to the bottom of the class for security than the top. Does it help your basketball team to pick a short kid when taller boys are on the bench? Not when I was at school.

Even when comparing products and vendors of similar security, if the buyer has little interest in security then adding more vendors to the list doesn’t help. Do you know which is more fuel-efficient out of a Ferrari, a Lamborghini, and an Aston Martin? Nobody cares. What if we add a McLaren to the list? Still, nobody cares. 5G network equipment will be bought on price, on performance at the core task, and the vendor’s ability to supply and support that equipment at the level desired by the network operator. Security will not be a top consideration because neither the operators nor their customers will make it a top consideration. Let’s not kid ourselves.

If security was a top 3 concern of network operators there would be no need to involve the ISC. The market would sort it out.

It’s because these products aren’t designed as security-critical that the Cyber Security industry is kept so busy trying to build secure infrastructure out of (relatively) insecure parts. There are situations where vendor diversity improves security. Different scanning engines for malware. Different approaches to filtering network traffic. Pattern recognition trained on different data sets. Different implementations of cryptographic algorithms. Diversity in implementation, diversity in fundamental approach. Vendors with a product of similar quality competing on a level playing field with one another. This isn’t one of those situations. We aren’t buying an antivirus subscription.

Levels, Edges, and Cores

The ISC letter correctly asserts that “Edge” vs “Core” in 5G is an old way of looking at things. Part of what gives 5G its advantage is the fact that functions are more distributed and less centralised. The assumption that Edge somehow means “less important” is much less true in 5G than it was in 3G or 2G. The ISC says that the better distinction to make is not edge versus core but to distinguish between functions of the network and to protect each appropriately. One might imagine the management and security functions would be afforded more protection than the ordinary data transport function.

This is logical but in Information Security we know from bitter experience how controls fail, sandboxes can be escaped, side-channels exploited. Unexpected interactions between complex software components can defeat security measures designed to keep users, functions, or network traffic separate. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to impose such separation and levels of security, only that they are prone to failure. Sometimes this failure is sudden and catastrophic from a security point of view.

A single vulnerable vendor, function, or software component can easily become a Typhoid Mary in the network. While that software may not do anything important, the physical system upon which it sits may be performing other more valuable functions. It may present a convenient starting point for lateral movement to more critical parts of the network. This is where the logic of layers and levels meets the spectre of fallible hardware and software.

I’d rather attempt to enforce controls, compartments, and layers on a “robust base” than a fragile one. Even the best Cyber Security engineers can’t turn base metal into security gold. Plating is by definition thin. It wears off now and then. Sooner or later the base metal is revealed. Network operators can’t transform bad software into good.

I’ve not talked about the potential for a vendor to be a threat-actor, under the influence of one, or infiltrated by one. This post has only addressed the matter of product security and product quality up to this point. I’m going to address “Man In The Vendor” later because I consider it separate to ordinary product security and quality.

False Cause Fallacy

The letter states:

- Russia hacks UK networks.

- Russia doesn’t supply those networks with equipment.

- So equipment’s origin isn’t a critical concern for security.

What it should have said is that the supply of equipment isn’t essential for hacking a network. It can help. However, the letter was attempting to make a point in Huawei’s favour. At best this is a neutral not a positive. What if you were a foreign power? What if you wanted to hack the national mobile networks? Wouldn’t you rather have an equipment supplier on the inside to help? Even if you had to subvert that vendor before you could gain access to the eventual target? I’ll return to this in a moment with MiTV.

5G Isn’t For Intelligence Sharing

The ISC letter states that intelligence isn’t going to be exchanged over 5G. While superficially true, this statement is naive. That which begins on strongly encrypted, dedicated intelligence channels sooner or later is discussed in a text message, a voice call, a WhatsApp group, or an email forwarded late at night to some personal mobile device. Sometimes by ministers who should know better. Access individuals have been known to take photos of documents they wouldn’t be allowed to transmit, to read them outside of controlled environments. 5G is very convenient and convenience wins over security when ordinary people are trying to get work done.

If mobile networks had little intelligence value, why would the NSA bother with Angela Merkel’s Blackberry? Why do intelligence services pay a million dollars for zero-day vulnerabilities for iPhones? Why bother trying to read the Ambassador’s secret cables when you can just capture the Foreign Minister’s smartphone directly?

Mobile networks are national intelligence assets, whether we want them to be or not.

The subject of intelligence agencies and state interests brings me to those “Man in The Vendor” or supply chain attacks I mentioned. The letter doesn’t explicitly address MiTV. However, it’s a subject worth visiting in a calm and considered way.

Man in The Vendor

Man In The Vendor or Supply Chain Risk is a threat model where the equipment (or software) vendor is either malicious or has been infiltrated by someone malicious. It could be that the vendor’s devices were tampered with en-route to the customer. In MiTV the hardware and program code of the device works against your interest as the device owner and operator.

MiTV is difficult to detect and counter in enterprise environments and almost impossible in network operators. By definition, the network operator’s business is the shared use of that hardware and software. Customer traffic, management traffic, security-critical commands and data, all flowing through the same chassis, circuit boards, processors, and memory. You trust the system to keep them separate. With MiTV the system lies to you.

Fortunately, MiTV is not a threat that most companies need to worry about. Unfortunately, network operators are not most companies.

Mobile networks are national intelligence assets, whether we want them to be or not.

“Carriers are very good at understanding the security of their networks, and what types of traffic are flowing over it, and looking for anomalies.” - ISC Statement on 5G suppliers, 19th July 2019.

Carriers are very good at understanding those things that impact availability, performance, and billing. I won’t embarrass any particular network operator. All I’ll say is that I’ve been a part of many red team exercises over the years. Security has improved since 2G/GPRS days where merely owning a GPRS modem would initially land you on the management network, with the option of not swapping to the subscriber network. The reality is most network operators still have far to go.

If the ISC assert that MiTV is a manageable risk, they’ll need to explain how operators are to detect microcode changes in processors, transient alterations to firmware, and the addition of parasitic devices to circuit boards. They’ll need to explain how to detect and interdict covert channels. They’ll need to explain how to do this at a price and level of effort network operators can afford. Perhaps ISC’s answer is end-to-end strong encryption for everyone. Somehow I doubt it.

Any equipment from any supplier from any country could have a MiTV. We’ve seen supply chain attacks on US vendors by US intelligence in the Snowden leaks. The vendor doesn’t need to be complicit. We’ve seen the weakening of security standards at the standards body level. Vendors went ahead in good faith and implemented flawed NSA-devised algorithms which they believed to be secure. Perhaps I should popularise MiTS (Man in The Standard).

So MiTV is complex. This is before we consider the risk posed by any particular product or company associated with a particular country in a geopolitical context. There are few satisfactory technical solutions to the problem. Fewer still that are economically viable and operationally workable for a national mobile network operator. The best time to limit the potential for MiTV is at the point of product design. That point has long since passed for 5G. The network architecture and design stage is probably the second-best time, but it’s a distant second.

When considering Supply Chain Risk of this sort one is reminded that capitalism only really works when you can be fairly sure what you are being sold is not intentionally harmful to you.

It’s A Geostrategic Question

The subject of competition is visited in ISC’s letter. I suspect they dislike being put in this position. I suspect they lament the fact that there are only 3 credible suppliers today and one of them is 30% cheaper than the others. The software quality of that particular supplier is poor by their own assessment. Worst of all, their country of origin is causing all sorts of problems with the Five Eyes. I assume Five Eyes are concerned about a potential MiTV.

ISC’s desire to “create greater diversity in the market” is wishful thinking. There’s a reason why there are fewer than a handful of suppliers. If anything I’d expect the number to diminish further in the coming years.

Where I agree wholeheartedly with the ISC is that this is not a dilemma with a technical solution. This is a geostrategic matter. It’s one the UK is going to face again and again over the coming decades in all sorts of different technology areas. 5G and Huawei are only the beginning. I suggest the UK develops a framework for this kind of situation because it’s going to keep happening.

Let’s consider some geopolitical context.

The competition, Nokia and Ericsson, are behind Huawei in terms of maturity of their 5G product and the deployment of it. However:

- They are Finnish and Swedish headquartered companies respectively.

- Physically close, European allies.

- Broadly similar Western/Liberal Democratic view of the world.

- Broadly comparable national economies to the UK in productivity and development.

- Similar view of Intellectual Property law.

- Similar cultural lens through which trade is conducted.

- Sweden is a member of SIGINT Seniors Europe (SSEUR), Finland isn’t.

- The fate of Finland and Sweden will be a variation on the fate of the UK, because of these similarities.

Cisco is also behind Huawei in product and deployment. Apart from the obvious geographical differences, we can tick off most of the items above in their case. The US is of course, a member of Five Eyes.

By contrast, Huawei and China don’t tick these boxes and never will. If the first big myth dispelled by this post is that China can only copy, the second should be that China is somehow going to become more Western. It isn’t. China is on its own path and finding great success with it. The Chinese don’t aspire to a Western mode except where the reward for doing so might benefit their own national strategy. One thing politicians in the West are going to have to explain over the next 10 to 20 years is how the people with the “best system” got beaten by China.

They should probably start redefining “winning” now.

“Switching equipment technology is related to international security, a nation that does not have its own switching equipment is like one that lacks its own military." - Ren Zhengfei, CEO Huawei in conversation with Jiang Zemin, President and Secretary-General, Communist Party of China, 1994.

The ISC letter is at pains to point out that China would not consider a British vendor for its national 5G network. They have that luxury. Huawei has invested more in R&D than Ericsson and Nokia combined. It has contributed 3x as many documents to the standards body. It was able to demonstrate 30-50% less latency than competitors and certified bandwidth test results at a time when the competition was yet to even complete the test.

National Introspection

I like adaptive strategies, OODA loops, A/B testing. I don’t think the government does enough experimentation. But you can’t run a country on an OODA loop, at least not in anything other than a tactical sense.

There’s one aspect of this saga that’s rarely discussed. It’s the frame within which these events take place. If I were to pick one word to characterise UK national strategy over the last 20 years the word I’d choose is drift. We’re in a sort of interregnum between the end of one period and the beginning of the next.

In 2011 the all-party Public Administration Select Committee (PASC) wrote to the government asking important questions about national strategy4. I’ll quote one of those questions here:

“What is meant by “strategy” or “grand strategy” in relation to the foreign policy, defence and security functions of government in the modern world?" - Public Administration Select Committee, 2011.

The response to this and other questions was so poor as to cause the Cabinet Office to have a second go at it without being asked. The second response was just as bad but it was worded more carefully. MPs officially (and generously) described the result as “disappointing” in the record. Their report was clearer:

“Government has lost the capacity to think strategically.” - Bernard Jenkin MP, PASC Committee Chairman, January 2011.

Part of the reason why the UK in general and the ISC in particular finds this 5G review so vexatious is that government has lost the capacity to think strategically. This matter could and should have been resolved long before now. An early manager of mine once told me that a good consultant was “like a good surgeon, sometimes wrong but never in doubt”. The UK is in doubt and has been for years. Whether it’s wrong or not is something that we’ll learn in the coming decades.

Missed Opportunities

Huawei could have built more secure software. They are perfectly capable. They don’t just copy, they lead in many areas. They could have built the product with more thought given to MiTV concerns, although there would have been a significant impact of such design criteria. It would have likely made their product less price competitive and slowed down its development. They would still have faced hostility on national security grounds. To mitigate either of these problems now at this late stage is extremely difficult.

A cynic might suggest that if Huawei offered to build an assembly plant for 5G equipment in the UK, say in the North East, they could have helped their case. Whether or not this should have made a difference or not depends on the national strategy. Huawei books about $700M in revenue in the UK. Worldwide it employs about 200K people. That’s about $125K per employee. At that ratio of staff to turnover, one might expect 6000 UK employees. The company has 1400. These are vague numbers and easily explained away, but you can see where this argument might go.

I see no reason why Huawei alone should undergo scrutiny while the other would-be suppliers escape it. If you’re going to design and operate what amounts to a Commercial Evaluation Facility for 5G equipment, why not run every vendor through it? Quite apart from the improvement in product quality and security this might produce, it seems like a fair and transparent way in which to operate.

The greatest missed opportunity of all is the failure of the UK to develop a coherent national strategy for approaching such decisions. One which is open and transparent. Where to compete, where to cooperate, where to concede. A hierarchy of needs for the nation.

“If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favourable.” - Seneca.

One thing is for sure, you’ll fit a camel through the eye of a needle before you get China to go against its own interests. Particularly if you aren’t even sure of what your interests are.

-

Oral Statement by Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Jeremy Wright. 22nd July 2019. ↩︎

-

UK Cabinet Office. Fifth annual report for the Cabinet Secretary from the Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre Oversight Board. March 2019. ↩︎

-

UK Parliament Intelligence and Security Committee. Statement on 5G suppliers. 19th July 2019. ↩︎

-

Public Administration Committee, Government response on UK National Strategy ↩︎