750 words, 3 minutes.

The Case For Default Deny

What’s free, permanently reduces your exposure to a range of potential vulnerabilities, requires no maintenance, and takes only a few minutes to implement?

Most web servers are installed to serve content to unauthenticated users on the Internet. Most only have a finite list of URLs or a specific number of web apps. I’ve always thought it strange that they install in a default-permit mode. You have a tightly constrained list of URLs to serve. You have a largely unfiltered range of incoming IP addresses. There is probably no opportunity for user authentication. Why not begin with a default-deny stance? Think about all the other potentially bad things the server will do in the default permit state;

- Executing CGI examples you forgot to remove.

- Displaying management interface pages.

- Showing the server filesystem.

- Displaying an arbitrary file.

- Displaying information about the web server binary.

In a default-deny regime the server wouldn’t be able to do any of those things unless you expressly permitted them. We only wanted our 100 or 1000 URLs to be served after all. Nothing else. Fortunately we can achieve default deny on a modern web server like nginx with small one-time effort. First the preparation;

- Install and configure a working nginx web server.

- Install your content.

- Test everything works in default-permit mode.

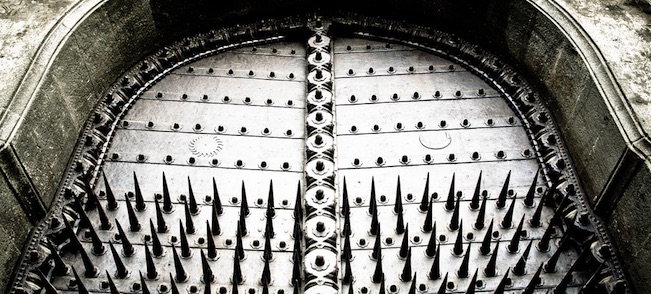

Close The Great Door

Now we add our default deny rule. This should prevent the web server from serving any content at all.

- Edit your nginx.conf.

- Add a ‘location / { deny all; }’ to your server config section.

- Reload nginx gracefully.

- Check nothing works.

Open The Wicket Gate

It’s time to open a gate for just the content we expressly permit. Requests for anything else, valid or not, will be refused with a 403 error. We are going to need a list of every URL to be served. I find most sites now have a sitemap.xml which lists all the browsable URLs. If you munge this file into a suitable format each time it’s updated, those URLs can be incorporated into an nginx.conf using an ‘include’ directive.

- Take your sitemap.xml (or other method for enumerating valid URLs).

- Munge it into a permitted-urls.conf file (might publish some bash script for this).

- Edit nginx.conf like this.

- Don’t put URLs directly in nginx.conf, use an ‘include’ statement.

- Reload nginx gracefully.

All that remains now is:

- Test thoroughly, especially if your site is complex.

- Automate-away the entire process.

Sleep Soundly (Like A Maratha)

You’ll never need to worry about accidents with test data left in the web page directory. You won’t suffer from vulnerable scripts/cgi which you forgot to remove or which were silently re-introduced after an upgrade or patch. Relax and enjoy the following advantages;

- It fails safe, if the URL file is bad or empty, nothing is served.

- With sitemap.xml the URL list is built for free by someone else.

- It’s simple to automate and easy to understand.

- Because nginx has graceful reload, you can do it frequently.

- It’s easy to have a layered defence (duplicate on Firewall/Load Balancer).

If you don’t run nginx I’m pretty sure all modern web servers support a similar setup. I’ll update this post with some properly formatted config-file samples later. I’ll post a script for handling sitemap.xml too.

Note: As it stands this configuration returns a 403 error (access denied) for any denied URL. If you don’t want to make it obvious that you have default deny, then you’ll need to translate that 403 “Denied” into a 404 “Not found”. This is also very easy on nginx;

- ‘error_page 403 =404 /404.html;’

Finally, I should point out that this configuration will not fix your vulnerable web applications. It will prevent the server from doing anything other than serving up approved pages or executing those apps. If your application permits either by design or accident something bad, it’s your problem. You may want to think about all the other enduring systems I recommend for Information Security. OWASP is a good place to begin.

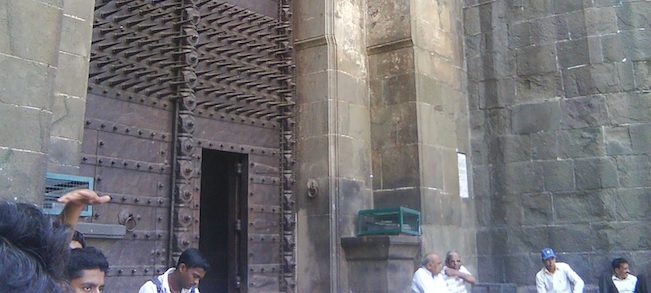

What About The Elephant?

The Peshwas of the Maratha Empire built Shaniwar Wada (Śanivāravāḍā) in 1732. They needed a door a battle elephant could pass through. However, this was a large potential vulnerability. Their solution was to install a Wicket Gate and other measures so ordinary every-day traffic could still flow. Absolutely no battle elephants unless by prior appointment. You’d be surprised how much secure design you can find in old forts. It’s almost as-if hundreds or thousands of years of accumulated wisdom went into their construction. Not to mention countless lives.