4300 words, 14 minutes.

This post was circulated privately in April 2020. Three months later the government announced that Huawei 5G equipment will be removed from the UK by 2027, a reversal of their previous position. I’ve updated the timeline with that development. Otherwise, the text is almost unchanged from the original. Keep that in mind. It follows my July 2019 post on the consideration the UK and its allies are giving to Huawei as a supplier of 5G mobile equipment. If you didn’t read that, now is a good time. - Nick Hutton, 29th November 2020.

Chinese men playing Go. Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Artist unknown.

4000 years ago the Chinese invented “Go”. Unlike Indo-European Chess, Go takes longer to play and uses a larger board. In Go, the goal is not to confront your opponent directly as one does in Chess. The winning system in Go is to surround them gradually and occupy their territory.

Current Events

In the nine months since my last post, the UK elected a Prime Minister, formed a new government, resiled from the European Union, and fought a global pandemic. However, we’ve struggled to reach a consensus on whether or not we should buy 5G network equipment from Huawei, a designated High-Risk Vendor. Here’s a summary of events since my last post:

- The government announced Huawei can supply up to 35% of edge (non-core) equipment to Mobile Network Operators.1

- NCSC’s Technical Director, Dr Ian Levy lamented the lack of 5G suppliers, endorsed the Edge vs Core distinction for improving supplier diversity, and endorsed technical measures as an effective strategy for mitigating the security risks.2

- USA, Australia, and New Zealand restated a commitment to ban Huawei from national mobile networks. Canada was “studying the British decision (to permit Huawei)”.3

- The EU released a toolbox for 5G to “identify a possible common set of measures which are able to mitigate the main cybersecurity risks of 5G networks.”4

- Parliament debated the security implications of the “up to 35%” decision.5

- I wrote this post and circulated it privately among interested parties.

- A Commons Defence sub Committee was convened to inquire into the security of the UK 5G networks.6

- MPs attempted unsuccessfully to have High-Risk Vendors excluded from 5G networks.7

- Huawei presented the ITU with a vision of an Internet where nation-states are the locus of control.8

- The US began requiring a license for the export of certain technologies that help foreign manufacturers produce semiconductors which are then sold to Huawei.9

- The Prime Minister instructed officials to draw up plans to reduce Huawei’s involvement in UK 5G to zero.10

- China’s UK ambassador said abandoning Huawei could jeopardise the UK’s new nuclear power plants and high-speed rail.11

- The government announced a ban on buying new Huawei 5G equipment after 2020 and ordered its removal by 2027.12

- NCSC’s Dr Levy blogged again, about how “everything had changed”. Huawei was out.13

- TikTok, the popular Chinese owned social media company announced it would scrap plans for a UK HQ.14

- Installation of new Huawei 5G equipment is to be prohibited after September 2021, earlier than anticipated.15

- As of 29th November 2020, UK network operators continued to buy and install Huawei equipment and contend that it will save them hundreds of millions of pounds compared to other vendors.

I’m going to talk about the UK’s strategy for dealing with High-Risk Vendors. First in general terms and then specifically about statements made by Dr Levy about Huawei before the UK’s eventual about-face. I’ll focus on the technical aspects of risk mitigation and in so doing move this discussion from the abstract to the concrete. Finally, I’ll attempt to place the UK’s strategy within the wider context of future UK/China relations.

Why after all this time are we still talking about Huawei?

Man In The Vendor

Supply Chain Risk or “Man In The Vendor” (MiTV) as I call it, is one of Cyber Security’s wicked problems. Wickedness isn’t about difficulty. Wicked problems are different because traditional processes can’t resolve them satisfactorily. They have countless causes or factors, are hard to describe, and don’t have a right answer. I use the term MiTV because “Supply Chain Risk” sounds like something you could dilute or diversify away. It sounds like something you could outsource or insure against. MiTV sounds like what it is. There’s a man. He’s in the vendor. He has something to gain from being there.

MiTV is hard to detect and counter in enterprise environments and very hard within mobile network operators. By definition, a network operator’s business is the shared use of that hardware and software. Different customer’s traffic, management traffic, security-critical commands and data, all flowing through the same chassis, circuit boards, processors, and memory. You trust the system to keep all this separate. When you have a MiTV, the system lies to you. - “The Eutopian. 29th July 2019”.

MiTV In Practice

Any vendor can suffer a MiTV. Most incidents go unreported. How does this man get in the vendor and what does he do? No need for abstract threats. We have real cases. We don’t even have to put ourselves in the mind of a foreign adversary.

- Vendors are pressured by governments to weaken their security.

- Supply chains are [compromised](https://web.archive.org/web/20200421225552/https:// arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2014/05/photos-of-an-nsa-upgrade-factory-show-cisco-router-getting-implant/) and hardware or software tampered with.

- Vendor operations are hacked.

- Sometimes the man isn’t just in the vendor, he owns it.

- Infiltration can be so deep that the man might as well be writing the vendor’s product.

- Sometimes the man is writing the vendor’s product.

Once a man is in the vendor he can tamper with the software, hardware, or firmware that makes up their product. He can introduce malicious code or physical components before, and sometimes after equipment enters service. Even cables can be turned against you when you can’t trust your supply chain.

Not only can a network operator’s equipment be made to lie to them, but it’s common for mobile network operators to outsource some of the build and management of their networks to the equipment vendor. The operator buys a package. Equipment, support, and services to keep it running. It’s convenient because expertise is hard to come by and such equipment needs frequent updates. These arrangements provide an opportunity for compromise of the network throughout its lifecycle. In these cases, the hardware or software product doesn’t need to be flawed or weakened when you buy it. It’s enough that the engineers managing it and the tools and systems they bring to that task can become vectors for exploitation or attack. Unwittingly or otherwise.

MiTV, An Adversary’s Long Term Strategy

MiTV has long-term advantages for the adversary. It’s something he can invest in because it pays regular dividends in the long run. It provides persistent access to information and systems in a way that’s hard to prevent, hard to detect, hard to shut down, and hard to trace back to a particular moment in time. While the adversary is in the vendor and the vendor’s product is in your network he gathers sensitive information, collects credentials, and profiles users he can then target to further his mission. Or just bides his time, knowing that he can activate his implant at a time of his choosing. It’s for this reason that such programmes are so valuable to intelligence agencies and their existence remains such a closely guarded secret, even years after they’ve stopped producing operationally useful information.

The man in the vendor isn’t always a state or state-affiliated. However, they tend to be more patient, better funded, harder to detect, and more likely to be interested in specific information or a specific class of target than most. MiTV is a tactic employed by states with a tier-1 offensive cyber security capability. This means the US, UK, Russia, Israel, and of course China. This list isn’t exhaustive. My first MiTV was in the 90s and probably French. They were replacing router firmware with a modified version to gain access to a negotiating team within a large defence contractor. That said, attribution was then as it is now, difficile.

It’s these kinds of threats posed by these actors in general and (one presumes) China in particular that Dr Levy said in January could be countered with technical measures. Measures like limiting Huawei to peripheral (non-core) parts of the network. Measures like network segmentation, anomaly detection, and integrity checking. Measures presumably implemented and operated by security teams at national mobile network operators. Three, O2, Vodafone, and EE. Companies that despite the efforts of their security teams, are hacked regularly.

Remember, individuals within security teams at mobile operators are drawn from the same pool of people that failed to even detect APT10’s multi-year Cloud Hopper operation.

The Odds

Cyber Security isn’t a numbers game, but Foreign Policy magazine estimates China’s “hacker army” at between 50,000 and 100,000 people. It’s against this army that security teams at national mobile operators will be pitted. Are already pitted. Regardless of whether or not such an army is granted a strategic advantage by the presence of Huawei hardware and software. The supply chain to which they may or may not have special access.

Installing 3rd party security solutions on top of mobile network assets (if such solutions were available, which they are not) offers no meaningful assurance against a MiTV. The first thing a MiTV does is prevent its detection by subverting any direct method of observation. Detecting a MiTV is a little like trying to spot a stealth aircraft using the “hole” in the picture where the object is, or the airflow disruption it leaves in its wake. Hard to sense directly. I’m highly critical of analogies in cyber security, so I won’t labour this one further. Suffice it to say that many MiTV operations have only been discovered because the “man” made a mistake. A slip-up. The slip-up leads to an anomaly. The anomaly caught the eye of a curious analyst. The analyst kept digging and uncovered an incident. Sometimes the incident only becomes apparent years after the initial attack and only through deductive reasoning or correlations made possible over time. Finally, there are those MiTV operations that one only becomes aware of when the adversary is compromised and their past and present activities become known.

The odds of detecting a MiTV are not good. We’ve always known this.

High-risk vendors carry among other risks, a higher risk of MiTV. The prospect of a MiTV presents a difficult problem. Difficult becomes wicked when great power politics, the opaqueness of complex technology, and the potential for market dominance all converge as they have done with 5G. Why do I. say this?

- Because it’s reasonable to think the vendor has an incentive to cheat.

- Or their government does.

- Since both known and unknown quality and security problems with their product provide ample cover for activities 1 and 2.

- Because those activities have a low risk of detection.

- Because customers lack either the skill, opportunity or financial incentive to detect them. Either at the point of product delivery or continuously throughout their service life.

“The future of telecoms in the UK”

“NCSC Technical Director Dr Ian Levy explains how the security analysis behind the DCMS supply chain review will ensure the UK’s telecoms networks are secure – regardless of the vendors used.” - The future of telecoms in the UK, Dr Ian Levy. 28th January 2020.

There’s much to agree with in Dr Levy’s January post. Huawei is a high-risk vendor. A special kind of high-risk vendor. One that requires extra caution. Why? Because they have limited competition (due to market dominance). Because of their strong position within all parts of the mobile network. Because of the poor quality of their software from a security perspective and their inability or unwillingness to improve it. Because of the long service life their products have. Because after 8+ years of work the HCSEC still didn’t know if the source code they were shown was the code in the shipping product.

To this, I add the fact that the company has a close association with the Chinese government. A government that is engaged in a decades-long campaign of Intellectual Property theft against UK companies. Companies like Rolls Royce, BAE Systems, and the whole of our financial sector. A campaign which successive UK governments have completely failed to push-back on. A campaign against companies that represent the material of the future growth in productivity, exports, and prosperity of this country and her people. Dr Levy didn’t mention any of that, but then I’m afforded greater latitude than he.

I also agree that in general, the way you improve the security within service provider networks is as the NCSC describes in their document “Summary of the NCSC’s security analysis for the UK telecoms sector”.

Fantasy & Reality

Where we disagree is in thinking such a framework has any chance of countering a determined and sophisticated supply chain attacker. Such an adversary has a wealth of options. From targeting hardware to software to services procured by the operator. They may target the very individuals who configure and manage the network. A network composed of hundreds to thousands of network elements, each with several processors, subsystems, firmware stores, channels, side-channels, and many, many, layers of software and configuration, virtualised or otherwise. It isn’t strictly necessary for the attacker to have the cooperation of the vendor, but it helps.

In December 2018 32 million UK mobile subscribers had their service disabled by a single expired digital certificate in a bad software update. The outage lasted 2 days. It was easy to diagnose and found to be accidental. Incompetence rather than malicious intent. It was an indicator of the fragility of mobile networks. It shows the lack of oversight from the operators and the complete absence of even the most basic testing. The idea that the same operators are going to detect and eject a serious adversary is a fantasy.

Operating cadence, business model, and financial constraints will frustrate mobile operator’s security team’s efforts before they so much as configure a VLAN, verify a firmware checksum, plug into a JTAG header or (who are we kidding?) X-ray a backplane. On what schedule are these teams going to take critical systems out of service for blueprinting? How long will it take to properly analyse one system? How many such systems must be deployed? How often should each be re-examined for deviation from the blueprint during its service life?

What’s puzzling is that Dr Levy surely knows this and yet states that the threat can be adequately mitigated by technical means. This is all the more surprising given the ban already in place for ZTE, another similar vendor. ZTE has a slightly different corporate structure from Huawei. ZTE also didn’t employ several civil servants and advisors from the Cameron government. Make of that what you will.

“The NCSC assesses that the national security risks arising from the use of ZTE equipment or services within the context of the existing UK telecoms infrastructure cannot be mitigated. The NCSC’s advice to operators in relation to ZTE has not changed as a result of this analysis.” - Summary of the NCSC’s security analysis for the UK telecoms sector, January 2020.

For any serious threat actor, gaining persistent access to a mobile network is a properly resourced campaign driven by a strategy. It’s not a point-in-time activity that can be countered with some controls and a mix of analysis and mitigations. The attack surface is too big and given the complexity of 5G networks, almost fractal.

Dr Levy knew this too. He needed to look no further than the work of his colleagues. As I said previously, if you’re a foreign adversary you don’t have to have a pliant (or vulnerable) supplier in the chain. It helps though.

“Looks like BritFone followed the NCSC’s security guidelines, better wrap it up, guys. Someone email the Director the bad news.” - Said no serious threat actor ever.

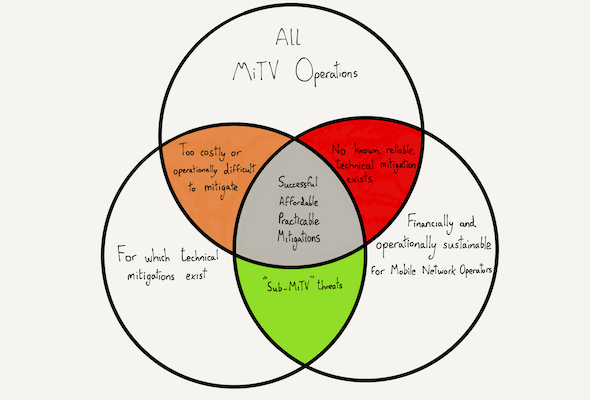

I presume Dr Levy thinks the common set in the centre of this diagram is far larger than I do. I think it’s more technically challenging, less affordable, and less operationally practicable to achieve meaningful mitigations against the kind of adversary the UK fears the most. I base this upon practical experience working with mobile operators, in investigating Advanced Persistent Threats including Supply Chain Attacks or MiTV, and as someone who once had profit and loss accountability at a publicly quoted fixed-line network operator.

The NCSC had concluded that the risks associated with High-Risk Vendors in general and Huawei, in particular, could be adequately mitigated by technical means, by restricting the vendor to 35% of the network, and by excluding them from certain specific areas. As far as I was concerned it was a mistake. A naive conclusion that failed to take into account technical and economic realities, while appearing reasonable and fair to anyone not charged with making the decision work in practice.

It’s a conclusion one might reach by credulously accepting assurances from executives at the mobile network operators. The guys wanting to save 30% off their CAPEX. The guys who were taken out by one expired digital certificate. Those guys. But this story doesn’t end here.

“NCSC Technical Director Dr Ian Levy explains the technical impact of the recent US sanctions on the security of Huawei equipment in the UK.” - A different future for telecoms in the UK, 14th July 2020.

In May 2020 the US announced a change to their export control rules. The change meant that no company would be permitted to ship chips to Huawei (even if Huawei-designed the chips) if US technology was used either in the design or manufacturing of them. Given the widespread use of US technology in the EDA toolchain this is an enormous handicap for Huawei. Without US technology and the decades of investment that went into it, it will be very hard for Huawei to produce high performance, low cost, highly reliable chips. Dr Levy’s blog of the 14th July 2020 provides a good summary of this change.

In that same blog, he reverses his previous position on the use of Huawei within the UK’s 5G networks. He says that the anticipated results of this change to US export controls will tip the balance against Huawei, making their products too risky for the UK. Mobile operators have until the end of 2020 to buy the equipment. It must be gone from national 5G networks by 2027, leaving them 7 years to recover the cost.

I’ll take the liberty of paraphrasing Dr Levy’s argument here. Huawei’s product quality (of which security is an aspect which the NCSC already said wasn’t good) is predicted to get worse. Worse to such a degree that where it was previously an acceptable risk, now it isn’t. It’s worth pointing out that it hasn’t worsened yet. Restrictions have only recently been enacted and Huawei claims to have a stock of parts, but in the future, it will probably worsen. China has of course been working to acquire its own EDA tools (EDA tools are strategic software) but as of this moment, there’s a gap. That gap is to the detriment of product security.

In my opinion, Dr Levy appears to reach the right conclusion for the wrong reason. Said another way, he’s right by accident. Huawei’s product quality (including security) might decline further. The UK might have even less visibility into the semiconductor IP used in those products than it currently does. However, this implies there’s sufficient visibility into Huawei’s semiconductors today. Presumably this includes any “special parts” that might find their way into the mobile operator supply chain, either before or after installation in UK networks. How much of a risk does he expect Huawei to become in the future (minus US semiconductor tools) versus today? Does it go from a 7 to an 8? An 8 to a 10? Is 9 the cut-off point for a ban? Where was China’s other network equipment firm, ZTE, on this scale when it was banned?

“NCSC assess that the national security risks arising from the use of ZTE equipment or services within the context of the existing UK telecommunications infrastructure cannot be mitigated." - Dr Ian Levy, NCSC, 1st May 2018.

If US restrictions are ever lifted as they might be by future administrations, what does that mean for the UK? Does this mean the Edge vs Core distinction and network operator mitigations are once again sufficient for the NCSC?

Final Thoughts

We don’t know the details of the UK’s internal discussions on Huawei. All we have are the signals from successive governments. Cameron, May, and Johnson all flipped from positive to negative in a cycle that repeated at least twice. Will there be a 3rd reversal? According to Dr Levy, it’s US action that tipped the scales this time. They could tip again. That’s a problem.

“This can only mean one thing. Politicians, trade envoys, the security services, and vested interests are all pulling on the ship’s wheel. I suspect they lack even an agreed framework for getting to a decision.” - Huawei 5G, The Eutopian, July 2019.

I don’t really think Dr Levy was “right by accident”. His blog is just the visible portion of the conflict, paralysis, analysis, hedging, and reactive balancing act the British state is attempting. Ministers and Members of Parliament are only now beginning to realise the significance of events long past. The events that brought us to this point. Meanwhile, the UK continues to play Chess while all along the game is Go.

In 1907 a Hungarian-born British archaeologist was exploring caves in the Gansu Province of Western China. He discovered a 6th-century manuscript. It was the earliest surviving manual for Go. In that manual was a chapter, 碁病法 (Go Faults). According to this historic text, there are several serious mistakes a Go player can make.

- Sticking too close to the edge and corners of the board, not moving into space, limiting opportunity.

- Clumsily responding to an opponent’s moves.

- Allowing your groups to be cut off from each other.

- Playing a stone hurriedly without thought.

- Trying to save a group that is already dead.

- Knowing when you are in a weak position and not being greedy.

- Knowing when you are in a strong position and not being timid.

How many of these mistakes has the UK made over the last 20 years?16

To what extent has the country been absent from the centre of the board? How clumsy were her moves and reversals? What’s the risk that her partners may be “cut off” from each other by decisions on this matter? How has the UK’s position of weakness (or strength) influenced this decision? Is the UK overplaying or underplaying her hand?

This post was about just one decision. One company. A single technology cycle for that company. The UK has placed one stone on the board. That stone is part of one group.

“The greatest missed opportunity of all is the failure of the UK to develop a coherent national strategy for approaching such decisions. One which is open and transparent. Where to compete, where to cooperate, where to concede. A hierarchy of needs for the nation.” - Huawei 5G, The Eutopian, July 2019.

The UK will face dilemmas like this continuously now. Not only in Telecommunications but in a dozen other “groups” where lawmakers suddenly discover what they thought was just another sector and just another product is somehow strategic according to some reckoning.

The best time to learn how to play this game was 20 years ago when it started. The second best time is now.

-

New plans to safeguard the country’s telecoms network and pave way for fast, reliable and secure connectivity. Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, National Cyber Security Centre, and The Rt Hon Baroness Nicky Morgan. 28th January 2020. ↩︎

-

The future of telecoms in the UK. Dr Ian Levy, NCSC Technical Director. January 28th 2020. ↩︎

-

Canada, isolated over Huawei 5G, is studying the British decision. Reuters. January 28th 2020. ↩︎

-

Cybersecurity of 5G networks - EU Toolbox of risk-mitigating measures. Cybersecurity & Digital Privacy Policy (Unit H.2). January 29th 2020. ↩︎

-

Security implications of including Huawei in 5G. Westminster Hall. 4th March 2020. ↩︎

-

Defence Sub-Committee, House of Commons. 6th March 2020. Q&A Session 28th April. ↩︎

-

Telecommunications Infrastructure (Leasehold Property) Bill and subsequent Debate. 10th March 2020. ↩︎

-

China and Huawei propose reinvention of the Internet. Anna Gross and Madhumita Murgia, Financial Times, 27th March 2020. ↩︎

-

Commerce Addresses Huawei’s Efforts to Undermine Entity List, Restricts Products Designed and Produced with U.S. Technologies. 15th May 2020. ↩︎

-

Boris Johnson to reduce Huawei’s role in Britain’s 5G network in wake of coronavirus outbreak (Telegraph). 23rd May 2020. ↩︎

-

China threatens to pull plug on new British nuclear plants. The Sunday Times. 7th June 2020. ↩︎

-

Huawei to be removed from UK 5G networks by 2027. Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport 14th July 2020. ↩︎

-

A different future for telecoms in the UK. Dr Ian Levy, NCSC Technical Director. 14th July 2020. ↩︎

-

TikTok’s UK headquarters in doubt amid US pressure BBC News. 19th July 2020. ↩︎

-

Huawei 5G ban brought forward to September. The Telegraph, 28th November 2020. ↩︎

-

˙ɯǝɥʇ ɟo ll∀ :ɹǝʍsu∀ ↩︎